The students at Amisted Elementary School, Kennewick WA, are preparing a virtual time capsule to pass on something from our times to an unknown future generation. Deciding what to put into such a capsule, as well as what form such a capsule should take, will be challenging. This essay is an adaptation of a multimedia presentation I made to the class sharing some ideas taken from my own work as an artist, art historian and collector, to get the students thinking about some basic issues of cultural value, identity, and preservation.

Philip E. Harding - March 24, 1997

How do we determine meaning? How do we measure value? What do we do with those objects, places, and ideas that are important to us - both as individuals and as a civilization - so that their meaning and value is maintained?

The two dolls on the right were purchased in Nairobi, Kenya. Each reveals something different about the culture and the motivations of craftsmen. The one on the left is a true ethnic art. It was made by a member of the Turkana Tribe from Northern Kenya, and shows a girl in traditional Turkana dress who has reached the age where she is now old enough to be married. The style is very abstract. The face is flat with angular, mask-like features showing no expression of individuality or emotion. The remaining arm is very thin and was never given a hand. In contrast the breasts, belly and hips have been emphasized because these features are important to giving birth and raising children. The chances are good that this doll was made with a specific girl in mind - perhaps by a member of her own family - not simply as a toy to be played with but as a sort of fertility figure. At some point, the girl grew up and the doll was no longer wanted. The doll may well have had its arm deliberately broken off to release its spirit or magical powers before being sold to a souvenir dealer. Eventually it reached the streets of Nairobi where it was sold to me.

Two Kenya dolls, left - ethnic, right - tourist

The figure on the right was also purchased on the streets of Nairobi, but it is not possible to determine which tribe or region of Kenya its craftsman came from. This is tourist art. It is done in a more modern, more realistic style. It presents a caricature of an African woman carrying a pot on her head. While her arms are also thin in proportion to her figure, this artist has not emphasized the woman's breasts and belly since this would be considered immodest to most modern Western viewers. The craftsman has carved the figure out of ebony because tourists will pay more for ebony. He has given the work a flat base so that it can stand upright on a tourist's table or fireplace mantel. In short, the figure on the right was made in order to make money from tourists and expresses little or nothing of the artist's traditional cultural values.

So what are these two figures worth and how is their value measured? If measured in dollars as charged by Nairobi street vendors in the early 1980's then they are worth about the same - around ten US dollars. But if we measure them for their ability to express cultural meaning and the values of those who created them, then the Turkana doll is clearly more valuable. From a cultural standpoint it is a truer, more honest work of art.

While I was in Kenya my father and I were invited to visit a clan of the Massai tribe in Southwest Kenya. This clan lived so far out in the African bush that they had spent days clearing a path just so our truck could reach their village. When we met the village elders under a flame tree, the oldest member of the tribe gave my father a stick. All Massai elders carry such sticks, just as their warriors carry spears. Therefore, in giving a stick to my father, they were embracing him as an honorary Elder in their clan. So how much is this stick worth? To talk about it in terms of dollars is meaningless. One might sooner ask, "what is the value of a Massai Elder?" This simple stick could properly be called "priceless." An object does not become priceless simply because it is rare or old or made by a famous person. An object is priceless because it has certain associations which give meaning and value that cannot be measured in dollars. These associations may be personal or something a whole nation or culture values.

Massai Elders presenting a stick to my father.

Jaqueline Kennedy with faux pearls.

Reliquary containing the Chains of Saint Peter

The Great Stupa of Sanchi

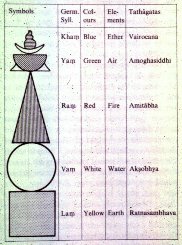

Symbolism of Tibetan stupa

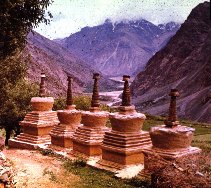

Tibetan

Stupas

Tibetan

Stupas

The evolution of stupas into pagodas

Ise - aerial view

Ise - ground level view

So how does one venerate a god, or the gift of a god, that is a symbol of an imperial clan? At the Naiku, or inner shrine at Ise, the mirror is placed in a wooden container shaped like a boat, inside a raised floor sanctuary, surrounded by four concentric fences. Only priests who have ritually purified themselves may, on special occasions, enter the compound. What is perhaps most interesting about the shrines of Ise is that at the Naiku (inner shrine), the Geku (outer shrine), and several of the subsidiary shrines, there are two identical sites that sit side by side. Every twenty years these shrines are completely rebuilt in every detail on their adjacent sites. The holy artifacts are then moved to the new buildings and the old shrines are taken down. This practice has gone on every 20 years since the 7th Century and has helped to preserve a living example of early Japanese architecture. Perhaps more important, the rebuilding allows each new generation of Japanese people to reconnect with their own ancient traditions in a way that simply visiting the shrine would not. It enables them to become part of their history and to help pass it on to another generation. If the purpose of a shrine or reliquary is not simply to set aside an object of value, but to pass on some values and traditions for future generations to remember, then the Grand Shrines of Ise has succeeded.

Freedom shrine

Similarly, Hindus built temples that also represent the universe. It is believed that at the center of the universe is the mythical mount Meru, which is home to the gods. Therefore, over the sanctuary of every Hindu temple, towers a model of this mythic mountain.

Hindu Temple

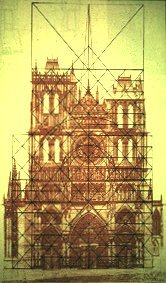

During the Middle Ages, builders designed cathedrals combining idea of the "New Jerusalem," or city of heaven, as described in the Book of Revelation, and the idea of Noah's Ark. The word "nave" which is used to describe the central space of the sanctuary, comes from the same Latin word as our word "navy" and suggests the cathedral was an ark or ship for transporting souls to heaven.

Athenian Acropolis

Gothic Facade geometry

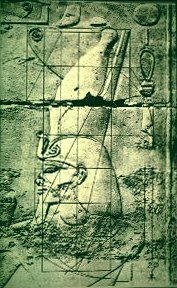

Egyptian Pharaoh

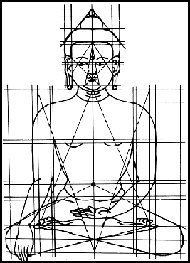

Geometry of Buddhist icon

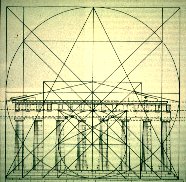

Geometry of Greek temple

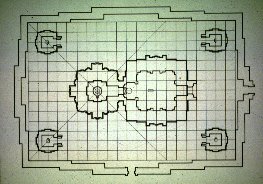

Geometry of Hindu temple plan

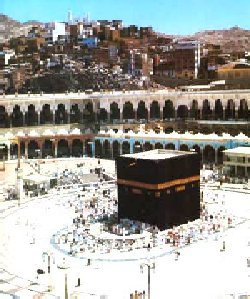

The Ka'bah in Mecca

Herod's temple

Herod's temple

Dome of

the Rock

Dome of

the Rock

Church of The Holy Sepulchre

When I visited Israel on a tour in 1983, my own sense of values was assaulted. Our bus took us past troops, tanks, prisons and mine fields. At the sea of Galilee we stayed in a luxury tourist hotel surrounded by high barbed wire fences. Where the fences met the sea, there were piles of broken concrete and coils of barbed wire entering the water. This was not the image of the Holy Land I had developed as I listened to my father's sermons as a child. Who do I blame? Many people in Israel blame each other. I have to blame myself -- my own expectations and desires. My trip to the Holy Land in search of meaning and value made me, and my tourist dollars for which this hotel was built, a pawn in someone else's conflict.

Today when looking at objects of art, when looking at art history, and particularly when creating art objects of my own, I must not only consider the meaning and value it has for me, but I have to remember that other people's values are often quite different. Deciding what is meaningful and valuable, and then working to preserve or advance those values, often involves careful consideration and negotiation.